This is the third article in a series examining church governance, accountability, and the nature of congregational life in the modern era.

Let me start with an admission: I am hard on the American church. I'm aware of how I can come across, and I do wrestle with it. But mine are words of a devoted brother, not an enemy. Maybe that feels more aspirational than it is true, but that’s the course I’m trying to chart. I am not speaking against the church; I am pleading for her.

At her best, the local church is the fragrance of heaven on earth—there is simply nothing better. My desperate desire is to see her be all she was created to be, which in most cases means only getting out of the way.

If you believe this as I do, you’ll agree that we must take an honest look at the structures we’ve built around her and ask: are they maximizing her potency, or are they simply inviting in the aroma of the world, conflating her purpose with her performance?

To engage with this question is to seize what is, in my view, one of the great opportunities of our lifetime.

The Omnipotence Trap

The contemporary megachurch phenomenon represents one of the most significant developments in Protestant Christianity over the past half-century. With as many as 1,750 megachurches currently operating in the United States—defined as Protestant churches with regular pre-pandemic attendance of 2,000 or more adults and children—these institutions have fundamentally reshaped the landscape of American Christianity. Despite frequent negative press treatment, ranging from financial scandals to valid questions over responses to abuse allegations, the vast majority of America's largest churches set positive precedents in many important areas of ministry.

In the first two articles of this series, we examined the biblical foundations of congregational governance and the practical challenges that megachurches face in maintaining authentic democratic processes at scale. We've seen how the New Testament establishes clear principles for church authority, accountability, and the gathered nature of Christian worship, while acknowledging the legitimate complexities that arise when thousands gather under one roof.

Yet as we’ve examined these tensions, a deeper structural question emerged: Are we expecting (or passively allowing) our churches to be something they were never designed to be? When a single institution attempts to be simultaneously a place of intimate worship and pastoral care, a community outreach organization, a media ministry, an educational institution, a social service provider, and a hub for meta-ministries (often all at once on Sunday mornings), it creates what we might call the "omnipotence trap"—the assumption that because churches have the resources to do everything, they should do everything, all organized under one institutional umbrella.

Assumptions, of course, come with inherent risks, and the consequences can extend far beyond operational complexity. When churches become sprawling institutions that require hundreds of volunteers just to function, Sunday mornings are transformed from spiritual sanctuaries to logistical imbroglios. More critically, church members meant to gather in unified purpose and presence become ministry facilitators, often before they've been adequately discipled themselves. While the Great Commission's charge to “make disciples” might include managing volunteers and programs, it is certainly not limited to it, and in particular on Sundays, the Lord’s Days, the focus must be on, well, the Lord.

Church members need to be spiritually fed and refreshed, pastorally cared for, and formed as disciples, wholly for their own good, but also (and especially) before they can effectively serve others. This happens primarily through the irreplaceable functions of corporate worship, pastoral preaching, participation in the ordinances, and mutual encouragement—precisely the elements that get compromised when members miss worship to execute the program and pastoral teams become performers and crowd managers rather than shepherds.

The structural problems continue past spiritual formation challenges. Contemporary research reveals significant weaknesses in the megachurch model, which reflects something closer to corporate governance, with a CEO/President who also serves as Chair of the board of directors. This concentration of authority, most common in founder-led churches, creates inherent vulnerabilities to leadership failure, limited accountability mechanisms, and potential for abuse of power.

This is compounded by the celebrity pastor phenomenon. As Warren Cole Smith observes, "Most megachurch pastors are celebrities; they are recognized everywhere they go. But their very celebrity status tends to insulate them from people who will tell them the truth about themselves." When legal and financial structures further stifle accountability efforts, congregations risk becoming what Smith describes as "cults of their pastor's celebrity." If the brand sells and the numbers trend the right way, who are we to question “why?"

This concentration of resources and attention creates broader ecosystem problems. Megachurches often function as ecclesiastical gravity wells, drawing people, talent, and financial resources from surrounding communities and smaller congregations. The result is a hollowing out of local church capacity precisely where authentic community and pastoral care might be most naturally sustained. Meanwhile, the production values and programming expectations set by megachurches create an impossible standard for smaller congregations to meet, fostering a consumer mentality that equates spiritual maturity with entertainment quality and program diversity.

These challenges matter beyond individual congregations, too. The Hartford Institute for Religion Research's comprehensive 2020 study reveals that megachurch leaders continue to influence other church leaders both directly and indirectly through vision, values, innovations, priorities, conferences, books, coaching networks, podcasts, social media posts, and personal relationships. The structural decisions of these institutions are consequential for the broader Christian community.

In many cases, these practices have been ongoing for so long and are normalized to such an extent that congregants hardly have the presence of mind to consider whether that’s what they want in a church or to discern whether that’s what the church should be. Even if they could, they would still have no forum in which they could express these sentiments to the broader congregation. To raise an issue would require a grassroots campaign of impossible scale. It’s worth asking: is this a bug, or is it a feature?

Taken together, these issues create systemic vulnerabilities, both enabled by and exacerbating a more foundational crisis: a model of church life that has prioritized making consumers (measured in numbers) over making disciples (measured in transformation).

I propose a different path forward for the megachurch: a dual-entity model that preserves the essence of what Scripture calls "church" while enabling the expansive ministry impact that characterizes the best of megachurch innovation. It's a model that honors both the sacred nature of the gathered assembly and the legitimate desire to serve communities with excellence and scale. But this isn't primarily about operational efficiency, accountability, or oversight; it is an argument for restoring the soul of the Sunday morning experience. It is about ensuring that churches provide what their members so desperately need at their core: authentic worship that effervesces the soul’s purpose, pastoral care that tends to the flock, and discipleship that produces mature followers of Jesus.

How We Got Here

Before proceeding with structural critique and proposals for change, let me be clear about what the dual-entity proposal represents: not a condemnation of megachurch innovation, but a call to sharpen, refine, and build upon its successes. It's moving on with the good, and moving on from the bad.

The Evolving Church

Church history demonstrates that organizational evolution is not only normal but essential for continued faithfulness. This can be seen as early as Acts 6, when the apostles recognized that "serving tables" was interfering with their calling to "prayer and the ministry of the word." Their solution was simple and effective: create a separate leadership structure (deacons) for operational concerns while preserving apostolic focus on the irreducibly ecclesial functions of teaching and spiritual oversight.

This principle of functional differentiation became foundational to church development throughout history. The diaconate evolved to encompass a broader range of responsibilities, becoming a center for the church's diverse activities. In essence, the deacons became the visible hands and feet of the church in the community, while bishops, ministers, and pastors maintained focus on worship, teaching, and providing pastoral care.

The early church evolved from house meetings to basilicas, from informal leadership to episcopal structures, from local autonomy to conciliar cooperation. The Reformation prompted massive restructuring across all of Protestantism. American denominationalism emerged through centuries of organizational experimentation, with Baptist churches themselves evolving from persecuted house churches to sophisticated convention systems that coordinate global missions.

Each transition reflected a deeper understanding of how to be faithful in new circumstances. The early Christian emergence of specialized charitable institutions provides a particularly relevant precedent. The sophisticated guest houses, hospitals, orphanages, and schools that operated under the supervision of ministers and bishops, but with specialized governance and professional staff, demonstrated how broadly Christian activities could be separated from exclusively ecclesial functions without losing their Christian character or effectiveness. St. Basil the Great's “Basileias” exemplified this approach, creating a comprehensive ministry complex that included a monastery, hostels, almshouses, and hospitals while maintaining a clear distinction between ecclesial oversight and operational management.

The tech industry also provides helpful parallels. Successful companies regularly "refactor" their code, restructure their organizations, and spin off divisions. Amazon began as a bookstore and evolved into a technology infrastructure company. Google started as a search engine and developed into an alphabet of specialized organizations.

Today's megachurches have pioneered innovations that have transformed Christianity globally. The question isn't whether they should exist, but how they can evolve to address the structural challenges that success has revealed in its primary purpose as a church.

What Is the Church and What Does It Do?

You can argue that the New Testament presents a remarkably consistent picture of the church's essential identity and functions, even as it allows for considerable flexibility in how those functions are expressed across different cultures and contexts. This biblical foundation provides the theological framework for distinguishing between activities that are inherently ecclesial and those that, while valuable and Gospel centered, do not require the specific institutional framework of the local church to be effective.

The Church as Assembly

The word "church" itself—ekklesia—means "assembly" or "gathering." This isn't merely descriptive; it's definitional. Wherever you see the word “church” in your Bible, you are actually seeing the word “assembly.” The church exists, fundamentally, as a gathered people. Jesus himself affirmed this when he said, "For where two or three are gathered in my name, there I am among them." (Matthew 18:20).

This gathered identity shapes everything else about the church. Unlike other organizations that can function effectively through distributed networks or virtual connections, the church's essential nature requires intimate nearness. This doesn't diminish the importance of scattered ministry throughout the week, but it does establish gathering as the irreducible core of ecclesial identity. The early church's commitment to regular assembly, even under persecution, demonstrates the centrality of this function to Christian identity and practice.

Research on early New Testament church sizes provides important context for understanding this gathered identity. By the end of the first century, scholars estimate there were 7,000-25,000 Christians across the Roman Empire, organized in approximately 40-100 congregations. Growth occurred across hundreds of small communities, with each gathering typically comprising a few dozen believers. Larger urban centers had upwards of several hundred Christians, gathering in multiple house churches, and maintaining a loose but connected network within each city.

This historical pattern suggests that early Christians enjoyed, if not prioritized, intimate fellowship and personal discipleship over large-scale gatherings. Of course, size was also naturally limited by meeting spaces, pastoral capacity, and secrecy needs, with growth occurring through multiplication (new churches) rather than just addition (larger churches).

The biblical mandate for pastoral knowledge provides even stronger support for right-sized congregations. When Jesus declares "I am the good shepherd. I know my own and my own know me" (John 10:14), the Greek word ginōskō implies intimate, personal knowledge—not mere recognition. This same word describes marital intimacy in Matthew 1:25. A shepherd who cannot maintain a certain level of personal knowledge with each sheep falls short of the basic biblical definition of shepherding.

Consider the mathematical reality: if a faithful pastor spends just 30 minutes annually in meaningful personal interaction with each member, a congregation of 400 would require 200 hours—five full work weeks—just for minimal annual contact. This doesn't include sermon preparation, administrative duties, counseling, hospital visits, or community engagement. The numbers simply don't work beyond a certain scale.

The Non-Delegable Functions

Scripture and historic Christian practice point to certain functions that are inherently ecclesial—they cannot be delegated to external organizations without fundamentally altering the nature of the church itself:

Corporate Worship: The gathered praise, prayer, and adoration of God's people (Acts 2:42, 1 Corinthians 14:26). Corporate worship is not simply individual worship happening in the same location; it is the unique expression of the body of Christ gathered in unified praise and prayer. The "one another" passages of the New Testament—encouraging, exhorting, teaching, and building up one another—require physical presence and cannot be fully replicated through digital or distributed means. It is important to note that this does not preclude worship outside of the local church on the Lord’s Day, but that type of worship cannot replace corporate worship on the Lord’s Day.

Preaching and Teaching: The authoritative exposition of Scripture and doctrinal instruction (2 Timothy 4:2, Acts 2:42). While teaching happens in many contexts, the pulpit ministry on Sunday represents a unique expression of pastoral authority and congregational submission to God's Word. The gathered assembly provides the context for the Word to be proclaimed with authority and received with corporate submission to divine truth.

Administration of Ordinances: Baptism and the Lord's Supper serve as visible expressions of the gospel and markers of church membership (Matthew 28:19, 1 Corinthians 11:23-26). These cannot be delegated without losing their essential meaning as acts of the gathered church.

Church Discipline and Restoration: The process outlined in Matthew 18:15-20 culminates with "telling it to the church" because the gathered community holds the final earthly authority in matters of spiritual accountability.

Pastoral Care and Shepherding: While others may provide counseling or support, the unique pastoral relationship between shepherd and flock requires the intimate knowledge that comes only through sustained, personal relationships (1 Peter 5:2-3). This is distinct from professional counseling or social services, which can be provided effectively by qualified individuals outside the church structure.

Congregational Governance: In Baptist polity, the final authority for major decisions rests with the gathered church membership exercising collective discernment under Christ's headship (Acts 6:3-5, Baptist Faith & Message 2000). This function requires the presence and active engagement of the membership for deliberation, discussion, and decision-making.

These functions form the irreducible core of what it means to be "church."

The Church's Ordered Priorities

Scripture can be helpful when trying to establish a clear hierarchy of church priorities that compromise its primary calling:

Focused Corporate Worship - The gathered assembly for prayer, Scripture, and sacrament represents the church's highest calling (Acts 2:42, Hebrews 10:25). The early church's commitment to "devoting themselves to the apostles' teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers" establishes worship as the foundational activity from which all other ministry flows. If the Westminster Confession of Faith is to be believed, our chief end is to glorify God, and we achieve this explicitly through worship.

Discipleship and Spiritual Formation - Jesus' final command in Matthew was "make disciples" (Matthew 28:19), and Paul's pastoral letters consistently prioritize teaching, growth in godliness, and spiritual maturity (2 Timothy 2:2, Ephesians 4:11-16). Discipleship requires sustained pastoral relationships and intentional formation. The New Testament model emphasizes personal mentoring, small-group interaction, and individual attention.

Community Outreach and Evangelism - The church's witness extends beyond its walls through evangelism and care for the vulnerable (James 1:27, Matthew 25:31-46). This flows from, rather than competes with, worship and discipleship.

A guiding principle can therefore be inferred from this hierarchy: worship forms disciples, and formed disciples engage in mission.

What Lies Beyond the Church's Core?

This raises an important question: What about the many other good and necessary things that churches, particularly megachurches, often do? Community outreach, disaster relief, media ministries, educational programs, large-scale events, social services, meta-ministries, and advocacy work are all legitimate expressions of Christian faith and calling. The question isn't whether these activities are valuable—they clearly are—but whether they require the specific institutional framework of the local church to be effective.

Church history has already provided numerous examples of successfully separating broadly Christian activities from exclusively ecclesial functions. Even within Baptist history, the principle of organizational separation for ministry functions has deep roots. The 19th-century "society plan" for missions created organizations where membership and representation were based on financial contributions from interested individuals or auxiliary societies, rather than church members. Organizations like the American Baptist Home Mission Society operated with independence while maintaining accountability to supporting churches through financial relationships.

There’s always been room for many things on the ministry plate, but where do they all fit?

The Ministry Spectrum

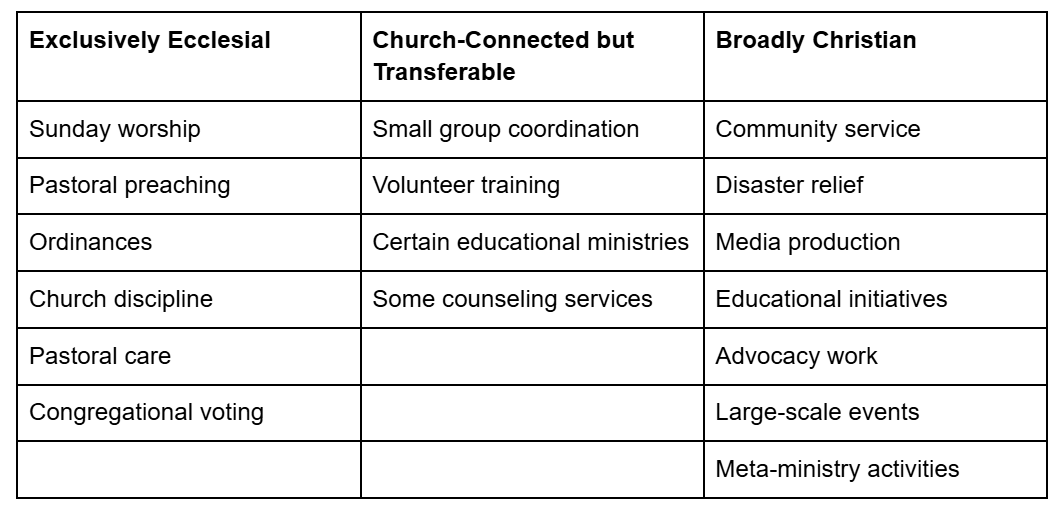

We can think of Christian ministry along a spectrum. At one end are activities that are exclusively ecclesial—they lose their meaning and authority if separated from the gathered church. At the other end are activities that are broadly Christian—they advance the kingdom and serve the common good, but don't require specific church authority to be effective. In the middle are activities that benefit from church connection but could potentially be structured differently.

This is certainly debatable, but still we must ask: where is the line that divides what’s for the local church and what is for the global ministry of all believers? Yes.

There’s no easy answer here. With so many nuances, the line is likely different across most churches. However, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, even if it's through trial and error.

This is likely a significant reason why churches have often assumed that, because they can do everything, they should. But this conflates the church's calling to be involved in all aspects of life with the assumption that the local church institution must directly control all aspects of ministry.

The church’s charge isn’t to do and facilitate all of these things for the people; it is instead to make disciples who do these things routinely in their daily lives. Church members should be formed in a way that ministry is lived out, not simply a program that is registered for.

That is the primary fruit the church should invest in and measure itself by. When the harvest of spiritual disciplines is found wanting, absent the church structures and programs, it should have the courage to hit pause and fundamentally reevaluate its direction. Protecting this primary investment in disciple-making is precisely the focus that a clear separation of church and ministry organization is designed to achieve.

The Current Megachurch Structure

Most contemporary megachurches operate under what we might call the "unified model"—a single legal entity (usually a 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporation) that encompasses all activities, from Sunday worship to community outreach to media production. This model has several characteristics:

Centralized Leadership: A senior pastor and staff team oversee all activities, from core church functions to extensive outreach programs.

Unified Budget: All resources flow through the church's financial systems, with internal allocations for different ministry areas.

Integrated Programming: Sunday morning often includes multiple services, extensive volunteer coordination, and various ministry activities competing for time and attention.

Single Brand Identity: All activities operate under the church's name and reputation, with varying degrees of direct pastoral oversight.

This model emerged naturally as churches expanded their influence and grew. It leverages the church's tax-exempt status, maximizes resource efficiency, and maintains unified leadership vision. For many contexts, it has enabled remarkable ministry impact and community transformation.

It may seem simple and straightford, but is that a good thing?

The Problems with the Unified Model

The unified model creates several persistent tensions that become more pronounced as churches grow larger.

The Gravitational Problem: When Churches Become Black Holes

Einstein’s theory of relativity describes how massive objects warp the fabric of space-time, bending everything toward their center. The more massive the object, the more intense the distortion—until, at a certain threshold, you get a black hole: an entity so dense that its gravity alters the path of everything around it, even light.

The modern megachurch, under a unified model, can begin to exert a similar gravitational pull, but its primary source of energy is its own congregation. As the church's size, budget, and operational complexity grow, so does its immense appetite for resources. It naturally begins to pull in ever-increasing amounts of volunteer hours, financial giving, and mental energy from its own members.

This is where the healthy dynamic of a church can cross a dangerous threshold. The problem isn't that people are serving or giving; that's the lifeblood of any congregation. The problem lies in proportion and purpose. When the institution's need to sustain its own mass becomes the primary driver, the flow of energy reverses. The church's purpose can subtly shift from building up its people to consuming their resources simply to keep the complex machinery running. This is how the gravity of the institution begins to distort the church's mission.

Members closest to this gravitational center can experience a kind of ministry "spaghettification"—they are stretched so thin across so many teams and responsibilities that their own spiritual formation feels shredded. They may arrive early for setup, serve through multiple services, and stay late for teardown, yet never truly worship as participants. Their discipleship risks dissolving into logistics.

But this gravitational pull also radiates outward, warping the entire local church ecosystem. Just as a black hole draws in matter from its surroundings, the megachurch often functions as an "ecclesiastical gravity well," pulling people, talent, and financial resources from smaller congregations. The result is a hollowing out of local church capacity, diminishing the health of the very communities that might otherwise sustain authentic pastoral care. Furthermore, the immense energy and light of its productions create an impossible standard for other churches to meet, fostering a consumer mentality that further accelerates the drain toward the larger gravitational center.

The pull also affects governance. As authority concentrates at the center, accountability can begin to diffuse. Genuine congregational oversight can be pulled inward, becoming more responsive to the executive vision than to the members themselves. The community that once gathered to seek God risks becoming a complex institution, one that orbits the strategy of its leadership.

Perhaps the most subtle danger is how this gravity doesn't just crowd out the church's essential functions, but re-purposes them. Even when inclusive of core church activities, the all-encompassing strategic vision can warp them into something else. Worship, intended as an encounter with God, may be reframed as a tool for visitor attraction. Discipleship, meant to form mature believers, can become a programmatic on-ramp for volunteer recruitment. In this environment, every sacred practice is subtly bent to serve the institutional mission. The Lord’s Day can feel less like a day of worship and rest, and more like the day of "Sunday Operations."

The danger here isn’t ambition—it’s unmanaged mass. When too much ministry, mission, and management accumulate under a single structure, the institution's gravity can become a threat to the church at its core.

The Shepherding Impossibility Problem

One problem is mathematical: pastoral care doesn't scale linearly. A faithful pastor can genuinely know, shepherd, and provide spiritual oversight to perhaps 100-200 individuals. Even with multiple pastors, the ratio quickly becomes untenable in a church of several thousand members. Yet the biblical expectation of pastoral knowledge and care remains unchanged (1 Peter 5:2-3, Acts 20:28).

Hebrews 13:17 warns that leaders "will have to give an account" for each soul under their care. The Greek apodidōmi logon implies a detailed reckoning—shepherds must answer for their knowledge of and care for each individual sheep. This becomes impossible when pastors oversee thousands they've never met.

Paul's pastoral practice demonstrates this principle. In Romans 16, he greets approximately 26 individuals by name, with personal details about many. His letters reveal intimate knowledge of individual struggles, gifts, and growth. Even Jesus, though he ministered to multitudes, chose only twelve for intimate discipleship and appointed seventy for broader mission (Luke 10:1).

In the context of the modern megachurch, however, we’ve often created a type of pastoral theatre—the appearance of shepherding without the substance. Members relate more to the Sunday persona of the senior pastor than to any actual pastoral relationship. We should be disappointed (not relieved) if our pastor doesn't personally know us. This isn't an unrealistic expectation—it's a biblical one. When Peter instructs elders to "shepherd the flock of God that is among you" (1 Peter 5:2), the Greek word for "among" (en humin) implies intimate presence and personal knowledge. Jesus himself models this in John 10:14: "I know my own and my own know me."

A shepherd who doesn't know his sheep isn't functioning as a shepherd.

Many megachurches attempt to address pastoral care through associate pastors organized by life stages—children's pastor, youth pastor, young adults pastor, families pastor, seniors pastor. While well-intentioned, this approach fragments pastoral knowledge in ways that undermine effective shepherding.

Consider a family with teenagers. Under the life-stage model, children might relate to the children's pastor, teenagers to the youth pastor, parents to the family pastor, and grandparents to the senior pastor. No single pastor develops a holistic understanding of the family's dynamics, challenges, or spiritual needs. When crisis strikes—job loss, serious illness, marital problems, teen rebellion—which pastor provides comprehensive care? How can any of them offer wise counsel when they only know fragments of the family's story?

And what of the church volunteer who gives their time to a ministry outside their age/stage demographic? Who is their pastor? This could be addressed with a cohort approach to pastoral care, but that’s a topic for a different post at a different time.

The Volunteer Exploitation Problem

The unified model also places enormous demands on volunteer coordination. Consider the irony: volunteers arrive early to set up for worship, serve throughout the service, and stay late to clean up, effectively missing the very gathering they're trying to make possible.

This volunteer exploitation problem reflects a deeper discipleship deficit. When members have been trained as consumers rather than disciples, they lack the spiritual foundation to understand the difference between serving the church's mission and serving institutional convenience. Undiscipled members often equate busyness with faithfulness, accepting volunteer demands that compromise their own spiritual formation because they've never been taught to prioritize worship participation and discipleship over operational support.

The unified model struggles to maintain appropriate distinctions between the sacred and the functional. When we require volunteers to miss worship in order to facilitate programming, we violate the historical understanding that prioritized the gathered assembly above all other activities on the Lord's Day.

The Accountability Diffusion Problem

In the unified model, the senior pastor and key staff must oversee everything from doctrinal teaching to community programs to operational logistics. This creates accountability challenges in two directions: leaders lack the time and expertise to provide meaningful oversight to all areas, while congregations struggle to exercise informed judgment about complex, multi-faceted operations.

The financial complexity of contemporary megachurches creates additional challenges for governance and accountability. With budgets often exceeding those of major corporations, these institutions require sophisticated financial management, oversight, and reporting systems. However, the unified model often obscures rather than clarifies financial priorities and trade-offs. When all activities operate under a single budget, it becomes difficult for congregation members to understand how their contributions are being allocated between core church functions and broader ministry activities.

This complexity gives rise to a paternalistic mindset, even among well-intentioned leaders. A belief can take root that the average layperson cannot possibly be informed enough to make wise decisions about intricate budgets, staffing, or strategic plans. This becomes a rather pathetic excuse for a lack of transparency. Decisions are made behind closed doors, and detailed budget line items are withheld from the congregation under the assumption that such information would only be misunderstood or cause unnecessary conflict. This practice, however well-meaning, fundamentally undermines congregational authority. It treats members as children to be protected from adult matters, rather than as co-stewards of the church’s mission, and it is precisely this diffusion of responsibility that the dual-entity model seeks to correct. Obfuscation by necessity can very easily become obfuscation by enmity.

Lack of discipleship only fuels this. Meaningful accountability requires disciples who understand biblical principles of church governance, pastoral authority, and congregational responsibility. When church members have been trained as passive consumers rather than informed participants, they are unable to provide adequate oversight, even when given the opportunity to do so. They lack the theological framework to evaluate whether leadership decisions align with biblical priorities, whether financial allocations reflect appropriate stewardship, or whether organizational complexity serves the church's mission or merely institutional growth.

Other problems include the creation of a professional clergy class that can stifle the ministry of the laity, a tendency to dilute theological depth for the sake of mass appeal, a financial gravity that pulls resources toward high-visibility productions at the expense of quiet mercy ministries, and a crippling institutional inertia that prioritizes self-preservation over faithful adaptation.

The Pseudo-Congregationalism Problem

A more subtle but equally damaging issue in the unified model is the erosion of genuine congregational authority under the guise of preserving it. Many large churches maintain the formal structures of congregational polity—deacon boards, elder councils, finance committees, and even occasional members' meetings—but these bodies cease to function as independent sources of accountability. Instead, they become rubber stamps for the centralized vision of the senior pastor and executive leadership.

In this pseudo-congregational system, committees are populated with individuals selected for their loyalty to the existing leadership rather than their ability to provide robust oversight. Agendas for members' meetings are carefully controlled, and complex issues are presented in ways that make assent the only practical option. The congregation is given the appearance of involvement without the substantive power to deliberate, question, or redirect the church's course. This creates a dangerous illusion of accountability. While leadership can claim that decisions were approved by the proper committees or the congregation itself, the reality is that the church's democratic process has been hollowed out from the inside, leaving the centralized authority of the pastoral team unchecked.

Cautionary Tales: When Unified Models Fail

Recent megachurch failures provide sobering evidence of these systemic problems. The concentration of authority without adequate checks creates conditions ripe for abuse and mismanagement.

Second Baptist Church, Houston: Perhaps the most instructive contemporary example is the ongoing crisis at Second Baptist Church in Houston. This Southern Baptist megachurch with 94,000 members and an $84 million annual budget recently faced a lawsuit alleging that church leadership "deceptively altered church bylaws to consolidate power, eliminate congregational voting rights, and potentially secure family control over the church's substantial assets, estimated at over $1 billion."

This illustrates the gravitational collapse perfectly—when a church reaches critical mass, the concentration of power becomes so dense that democratic governance cannot escape its pull.

The Pattern Across Megachurch Failures: An analysis of major megachurch collapses reveals consistent patterns directly related to problems with the unified model. Mars Hill Church (Mark Driscoll's power consolidation), Crystal Cathedral (Schuller family governance), Harvest Bible Chapel (James MacDonald's financial mismanagement), Willow Creek (Bill Hybels' unchecked authority), Hillsong (Brian Houston's financial impropriety), Gateway Church (Robert Morris), New Birth Missionary Baptist (Eddie Long), Oak Cliff Bible Fellowship (Tony Evans), and Synagogue Church of All Nations (TB Joshua) all demonstrate how unified structures enable small groups to control massive resources without effective oversight.

Potential Solutions: Alternative Structures

Recognizing these challenges, some churches have begun experimenting with alternative organizational structures. Each approach attempts to preserve the benefits of scale while addressing the inherent tensions of the unified model.

The Multi-Site Approach

Many megachurches have adopted multi-site models, creating multiple campuses with local pastors under centralized leadership. This addresses the shepherding challenge by reducing the size of individual congregations while maintaining unified vision and resource sharing.

Benefits: Smaller pastoral ratios, localized community engagement, preserved economies of scale.

Limitations: Often maintains the same structural problems at each site; can create confusion about congregational authority; pastoral authority becomes divided between site pastors and central leadership.

The Multiple Service Model

Others have maintained single locations but multiplied services, creating multiple smaller gatherings throughout the weekend. This allows for more intimate worship experiences while preserving unified leadership and facilities.

Benefits: More manageable crowd sizes, varied stylistic preferences, efficient facility usage.

Limitations: Fragments the congregation; reduces the power of truly corporate worship; multiplies volunteer demands; pastoral energy gets distributed across multiple identical services.

The Program Separation Model

Some churches have begun separating certain programs into distinct organizational entities while maintaining unified leadership. For example, schools, counseling centers, or community service programs might operate as separate nonprofits with overlapping leadership.

Benefits: Specialized governance for specialized functions; potential access to different funding sources; clearer organizational boundaries.

Limitations: Often lacks clear accountability structures; can create competing loyalties; may not address core issues of pastoral span and Sunday programming.

The Dual-Entity Model: A Different Approach

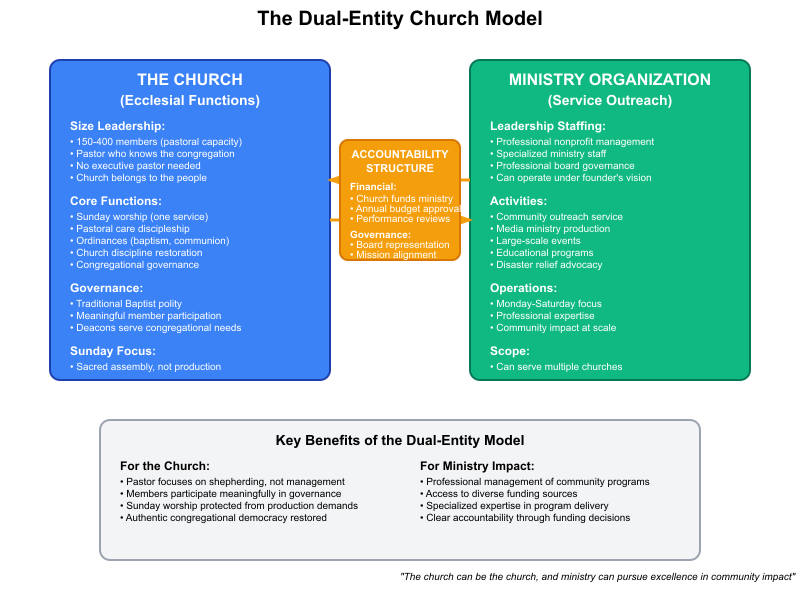

What I propose is a more fundamental restructuring: the dual-entity model. Instead of trying to manage complexity within a single organizational structure, this approach embraces the distinct nature of different ministerial functions by creating two separate but related entities.

The dual-entity model functions like a binary star system—two related but distinct objects that maintain their own gravitational fields while orbiting around a common center. The Church maintains its appropriate "mass" (size and scope), allowing for healthy pastoral relationships and congregational governance. The Ministry Organization operates within its own gravitational field, attracting resources and volunteers that are appropriate to its mission without distorting the Church's essential functions.

This prevents the formation of ministry black holes while preserving the benefits of both intimate church community and large-scale kingdom impact. Instead of one massive object that can distort everything around it, we get two appropriately-sized entities that can coexist without warping the ministry spacetime beyond recognition.

The Church Entity

The Church would be organized as a traditional congregational church with these characteristics:

Size: This should be limited to a number that allows for genuine pastoral care and congregational governance, which would vary based on pastoral capacity and community context.

Leadership: A pastor (or small pastoral team) capable of actually knowing and shepherding the congregation. Other leadership stewards can include deacons, elders, committees, etc. Critically, the church would be led by the people through democratic processes upon receipt of transparent disclosures.

Staffing and Compensation: The church employs essential pastoral staff (pastor, associate pastors as needed), administrative support, and key volunteer coordinators. Deacons serve in their traditional ecclesial role handling congregational care and administration within volunteer capacity.

Activities: Sunday worship, pastoral care, discipleship, church discipline, congregational decision-making, small group coordination, and programs manageable by volunteers without interfering with worship participation.

Schedule: One primary worship service where the entire congregation gathers together, embodying the "one assembly" principle that reflects the unity of the body.

Governance: Traditional Baptist congregational polity with meaningful member participation in significant decisions. Major decisions—including pastoral calls, budget approval, church naming and branding, and bylaw changes—would require both a quorum of at least 40% of active members and a supermajority vote (two-thirds) to pass. Members' meetings would occur quarterly rather than annually, with detailed information packets distributed at least two weeks in advance to enable informed deliberation. This intentional slowing of the decision-making process ensures genuine congregational discernment rather than rushed ratification of predetermined outcomes.

Biblical Budget Priorities: The Church's budget would reflect biblical priorities with clear allocations based on the vision and mission of the church, as determined by the membership.

Membership: Membership would be a formal covenant entered into by baptized believers who commit to the church’s faith and fellowship. To ensure this covenant remains a living commitment, it would be maintained with integrity. Therefore, membership could be dissolved not only through biblical discipline for unrepentant sin but also by a member's prolonged and unexplained absence from the church's core life of worship, fellowship, and participative governance.

Transparency: All aspects of the Church's life—from finances and budget decisions to membership matters and leadership meetings—would be conducted with the highest degree of transparency. Budgets would be detailed and accessible, and regular members' meetings would provide a genuine forum for discussion and decision-making, ensuring the congregation remains fully informed and empowered to lead.

The Ministry Organization

The Ministry Organization would operate as a professional nonprofit with these characteristics:

Mission & Activities: The Ministry Organization handles the full spectrum of kingdom work that, while flowing from a biblical worldview, does not require the specific authority of the gathered church. This includes community outreach and social services, but it is also the ideal engine for meta-ministries. This professional organization can host leadership conferences, manage pastoral coaching networks, operate internship and residency programs that train future leaders, and publish resources for a global audience. These meta-ministries require a level of operational and financial sophistication that is distinct from, and often disruptive to, the core ecclesial functions of a local church.

Leadership: Professional staff with expertise in nonprofit management, program delivery, and community engagement. Unlike the church, the ministry organization may operate under the vision and leadership of a founding pastor or leadership team—this structure can accommodate visionary leadership without compromising congregational democracy.

Staffing and Compensation: The ministry organization employs professional staff including program managers, community workers, media personnel, event coordinators, paid musicians and technical staff (when necessary for quality programming), communications specialists, grant writers, fundraising coordinators, and specialized ministry professionals.

Schedule: Primarily Monday through Saturday operations, with the flexibility to schedule programs before or after Sunday worship without interfering with the church's primary gathering.

Governance: Professional board governance with expertise in nonprofit management, community development, and organizational leadership.

The Connecting Relationship and Accountability Structure

The Church's financial support serves as the primary accountability mechanism. Rather than micromanaging operations, the Church exercises oversight through transparent funding decisions that reflect congregational approval of the Ministry Organization’s direction and effectiveness. The precise method for this financial support can vary, but it must always reinforce the principle that the Ministry Organization is accountable to the Church that founded it. Several models can be considered:

The Congregational Allocation Model: This is the most straightforward and stable approach. In this model, the Church leadership (Elders, Deacons, or a finance committee) proposes an annual budget in which a specific percentage or line-item grant is allocated to the Ministry Organization. This budget is then presented to the congregation for debate, amendment, and final approval. Accountability is exercised annually through this budgeting process, which requires the Ministry Organization to submit reports and demonstrate its missional alignment and effectiveness to justify its funding for the coming year. This method provides predictable, stable funding for the Ministry Organization’s core operations.

The Hybrid Funding Model: This model blends the stability of a congregational allocation with the direct engagement of members. The Church budget, as approved by the congregation, provides a foundational grant to the Ministry Organization to ensure its operational viability. In addition to this base support, the Church provides clear channels for members to give designated, above-and-beyond gifts to the Ministry Organization for specific, pre-approved projects or capital needs. The Church might facilitate this through special offerings or a "Ministry Partner" section on its online giving platform. This two-pronged approach ensures the Ministry Organization remains financially stable while also allowing the congregation to directly affirm and empower specific initiatives they are passionate about.

The Member-Directed Model: A more dynamic, though less stable, option is to allow individual members to direct a portion of their regular giving. Under this model, the Church establishes two distinct funds: a "Church General Fund" for ecclesial ministry and a "Ministry Organization Fund." Members can then make a standing designation (e.g., 90% to the Church, 10% to the Ministry Organization) for how their tithes and offerings are split. This creates a direct, market-based form of accountability; if the congregation is excited by the work of the Ministry Organization, its funding will reflect that.

Regardless of the model chosen, the key is congregational authority and transparency. This financial link is the sinew that connects the two entities, ensuring the professional ministry always remains rooted in and accountable to the worshiping community.

Governance Connections

While maintaining operational independence, several governance mechanisms ensure ongoing alignment:

Board Representation: The Church pastor (or designated representative) serves on the Ministry Organization board.

Shared Leadership: Ministry Organization leadership regularly attends Church leadership meetings to report and coordinate.

Theological Oversight: The Church retains authority to address theological concerns through board relationships and funding decisions.

Operational Boundaries and Cooperation

Resource Sharing: The two entities can share facilities, equipment, and certain administrative functions where efficient, governed by formal usage agreements.

Volunteer Coordination: Church members serve as volunteers with the Ministry Organization, but their volunteer commitments cannot interfere with their church responsibilities or Sunday worship participation.

Mission Alignment Verification: Annual reviews, tied to the funding process, include explicit assessment of theological and missional alignment.

If the Church's pastor also serves as the head of the Ministry Organization, it is essential that the two roles remain distinct. His compensation, authority, and accountability for each role must be handled separately by the respective governing bodies. The Ministry Organization's board must have full and independent authority over his employment as its CEO, including the power to redirect or even terminate that role, without affecting hi’s status as pastor of the Church. This ensures the Ministry Organization does not simply become an unaccountable extension of the pastor's personal brand.

The Future State: Implementing the Dual-Entity Model

How might this model work in practice? Consider this scenario that demonstrates the practical benefits and operational realities of the dual-entity approach:

Sunday: Sacred Assembly

On Sunday morning, church members gather for worship together. The pastor preaches to people he shepherds throughout the week. Members arrive as worshippers, not workers. The service includes baptism of new members whom the congregation has observed and approved, and communion shared by people who are genuinely in covenant relationship with one another.

Every member can participate fully in worship because no one is required to miss the gathering they came to experience. Children and adults worship together, experiencing the multi-generational nature of the church. Visitors encounter an authentic community where members are being spiritually formed rather than institutionally managed.

The pastor's attention is focused entirely on spiritual leadership—preaching that feeds souls, prayers that intercede for individual needs, and pastoral presence that provides comfort and guidance. Members receive what they came for: corporate worship, biblical instruction, pastoral care, and authentic Christian fellowship. They leave spiritually strengthened and equipped for service throughout the week, rather than exhausted from serving the institution during the time set apart for their own spiritual nourishment.

In essence, Sunday would be specifically set apart for corporate worship and giving God all of the glory, together.

Monday through Saturday: Kingdom Impact

Throughout the week, the Ministry Organization operates community programs, disaster relief efforts, media production, and large-scale events. Church members volunteer with these programs as they feel called and are able. The Ministry Organization employs professional staff with expertise in nonprofit management, community development, social services, and media production.

The pastor spends his time in study, prayer, pastoral care, and discipleship rather than managing complex organizational operations. Church members engage in genuine small-group Bible study and mutual care rather than endless committee meetings about programming logistics.

When the church considers supporting a new Ministry Organization initiative, the congregation can make informed decisions based on clear reports and their own volunteer experience rather than trying to evaluate complex operational details they don't understand.

Clear Benefits, Clear Mission

This dual-entity structure directly solves the key problems facing the contemporary megachurch:

For Pastors: Shepherds, Not CEOs. Frees pastors from administrative gridlock to focus on their primary calling: preaching, teaching, and soul care.

For Church Members: Spiritual Growth, Not Institutional Burnout. Sundays are restored as a time for worship and spiritual nourishment, not just volunteer shifts. Service flows from a full spirit, rather than being a prerequisite to it.

For Ministry Impact: Professional Excellence, Broader Reach. Allows the ministry arm to be run with professional management and specialized staff, opening access to diverse funding (like grants) and maximizing community impact without compromising the church's core mission.

For Accountability & Stewardship: Unprecedented Clarity. The congregation knows exactly where its money goes—to the church's essential functions or to support the separate ministry arm. This makes funding decisions a powerful and direct tool for congregational oversight.

For Scalability & Succession: Healthy Multiplication. Creates a natural pathway for church planting as congregations grow. It also drastically simplifies succession planning by creating two distinct and more sustainable leadership roles—pastor and ministry executive, rather than one impossible "visionary CEO" position.

Of course, no structural shift—however biblically informed or practically advantageous—will go unchallenged. Change invites scrutiny, and rightly so. Healthy churches should test ideas carefully, weighing them against Scripture, wisdom, and experience. We can do hard things.

A House Divided, and Thriving

Structural division typically signals weakness and, ultimately, collapse. Yet, for the modern megachurch, a deliberate, structural division is the key to spiritual vitality. The monolithic structure that conflates the sacred church with a complex ministry organization is already a house divided against itself—by competing purposes, conflicting leadership roles, and a confused congregation.

The dual-entity model offers a solution by creating an intentional and clarifying division. This is not a division of mission, but of function. It separates the covenant community from the service corporation, allowing each to excel.

This strategic separation is how the house thrives. It frees the pastor to be a shepherd, not a CEO. It frees the congregation from a consumer mindset, empowering them—as discipled participants—to exercise their proper spiritual governance. Most importantly, it frees the church as an institution to focus its energy and resources on its primary, God-given mandate: disciple making.

By dividing the administrative house, we allow the spiritual home to be properly ordered and unified in its sacred purpose. This structure provides clarity, restores biblical accountability, and unleashes the church to do what only the church can do.

It is a house strategically divided, not for ruin, but for a more resilient and faithful future.